Addressing Safety in Domestic Violence in Primary Care Peer Review

- Study protocol

- Open up Access

- Published:

Improving the healthcare response to domestic violence and corruption in primary care: protocol for a mixed method evaluation of the implementation of a complex intervention

BMC Public Wellness volume 18, Article number:971 (2018) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Domestic violence and abuse remains a major health concern. It is unknown whether the improved healthcare response to domestic violence and abuse demonstrated in a cluster randomised controlled trial of IRIS (Identification and Referral to Improve Southafety), a complex intervention, including general practice based training, support and referral programme, tin can be accomplished outside a trial setting. Aim: To evaluate the impact over four years of a organization wide implementation of IRIS, sequentially into multiple areas, outside the setting of a trial.

Methods

An interrupted time series analysis of referrals received by domestic violence and corruption workers from 201 general practices, in five northeast London boroughs; aslope a mixed methods procedure evaluation and qualitative assay. Segmented regression interrupted time serial analysis to guess touch on of the IRIS intervention over a 53-calendar month period. A secondary analysis compares the segmented regression analysis in each of the 4 implementation boroughs, with a fifth comparator borough.

Discussion

This is the first interrupted time serial assay of an intervention to ameliorate the wellness intendance response to domestic violence. The findings volition characterise the bear upon of IRIS implementation outside a trial setting and its suitability for national implementation in the United Kingdom.

Background

This paper reports the protocol for a system broad implementation evaluation of IRIS - Identification and Referral to Improve Safety of women affected past domestic violence and abuse (DVA), a complex intervention, designed to improve the primary healthcare response to DVA.

According to World Health System (WHO) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) guidelines, health professionals should be trained to provide help for women affected by DVA past facilitating disclosure, checking their safety, offering support and referral, and providing the appropriate medical services and follow-up care [ane, ii]. These guideline recommendations are based on enquiry from multiple wellness settings. This inquiry includes how to effectively identify those affected past DVA and record DVA safely, in emergency care [3], antenatal [4], maternity & sexual health services [five], HIV clinics [6], customs gynaecology [seven], mental wellness [viii] and principal care [nine]. Yet globally, clinicians often do not respond adequately to DVA [10]. In main intendance, effective clinical management of common conditions (such equally depression or unexplained hurting) is not possible if a patient's experience of abuse remains subconscious [11]. IRIS is an prove based innovative model of intendance that addresses this gap in healthcare provision and the suboptimal response to DVA in primary care [9].

The IRIS pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial in 24 intervention and 24 control full general practices, in two English language cities, showed a 3-fold difference in identification of women affected by DVA and a seven-fold difference in referral to specialist DVA services between command and IRIS practices respectively [9]. This was the first show that a system level intervention could better the healthcare response to DVA, past increasing the referrals made of women affected by abuse, to an IRIS advocacy worker (the advocate-educator). A Cochrane review shows that brief advocacy may reduce corruption, better mental health and quality of life, especially for less astringent abuse and in pregnant women [12]. IRIS with its focus on offer women referral for specialist DVA advocacy was also estimated to exist cost-effective [13]. Qualitative analysis nested within the original IRIS trial showed that women were positive about beingness asked about abuse past wellness professionals and contact with DVA advocates [14]. Health professionals viewed IRIS as an acceptable intervention but had a concern almost the iv hours' length of training [15]. Trial results showed a wide variation in DVA identification and referral rates between IRIS practices and amid clinicians within IRIS practices [9].

Based on the original trial, the IRIS model has been included equally an instance of best practise in multiple policy and guidance documents, including past Prissy [2], the WHO [one], the Uk government [xvi], the Chief Medical Officeholder [17] and the Home Office [eighteen].

DVA's health furnishings are more burdensome than hypertension, obesity, loftier cholesterol and smoking in women of reproductive age [19]. DVA is the pinnacle correspondent to death, disability and illness in these women [20]; its management in clinical practise warrants much greater attending. Gynaecological and sexual wellness problems are the virtually prevalent and persistent physical wellness consequence of DVA [21]. Long-lasting mental health problems include depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder - the almost prevalent mental health sequelae [22].

In the Britain, since the recession of 2008/09, violent crime against women has increased [23]. Yet between 2008 and 2013, funding for specialist back up services' has decreased by a third [24], despite DVA costing an estimated £11 billion in lost economical output, social services, emotional and medical costs in 2012 [25].

The IRIS programme was developed as a principal wellness care contribution to a societal response to DVA, linking general practice to DVA services. The training, back up and referral pathway is a circuitous intervention that enables clinicians to enquire about DVA, recognise the DVA in a woman's life, understand and be able to discuss with her that abuse's significance to her health whilst providing fantabulous clinical care, taking the abuse into account and offering a referral to a named specialist inside a DVA support service.

Despite the trial prove, the national policy documents supporting IRIS, and the initial commissioning of IRIS in 34 areas, we practise non know whether the programme is sustainable and effective when implemented outside the trial context. Nosotros need to decide whether IRIS and its original trial results tin be replicated in general exercise settings over the longer term. The UK Medical Enquiry Council advises "…furnishings are likely to be smaller and more than variable once the intervention becomes implemented more than widely, and…long-term follow-up may be needed to determine whether short-term changes persist" [26].

Methods

Chief objective

- 1.

To measure out the effectiveness of IRIS aslope a comparator intervention, in full general practice, both designed to better the healthcare response to DVA in primary care.

Secondary objectives

- two.

To empathise the process of IRIS implementation, using a mixed methods approach, including survey and qualitative information.

- iii.

To evaluate IRIS implementation, aslope IRIS' sustainability, with in depth case studies of two different IRIS areas using interviews, participant observation and document assay.

Pattern

A four year observational, businesslike, mixed methods, implementation MRC phase 4 report [27]:

The master blueprint is a segmented regression analysis of interrupted time serial (ITS) data (primarily, referrals received past DVA workers) from general practices that implemented the IRIS intervention and a comparator borough in which the general practices did not implement the IRIS intervention.

In that location are approximately 386,277 women, anile sixteen years and above (patients), registered at the 140 full general practices, in the four north-e London implementation borough sites (A, B, C & D), for which IRIS was commissioned; and approximately 77,464 women aged 16 years and in a higher place (patients), registered at the 61 general practices, in an adjacent comparator n-east London civic site (E). The comparator borough has not implemented the studied intervention (IRIS) but instead used an culling DVA initiative, during the time period examined.

Qualitative research is carried out in parallel, including a concurrent embedded, mixed-method process evaluation of IRIS implementation and 2 in-depth, local, IRIS case studies with a sustainability focus.

All results are integrated, by considering the quantitative and the qualitative results aslope each other, checking that results coincide (for instance, are areas with the highest incidence charge per unit ratios for referrals received as well the areas in which IRIS has the greatest training reach) whilst reflecting on discordant results, in order to increase agreement about IRIS implementation, sustainability and effectiveness.

Setting

This implementation evaluation involves viii sites. 4 of these are northeast London civic implementation sites (A, B, C & D) that commissioned IRIS within the study menses. One is a comparator northeast London civic site (E) that did not commission IRIS but an alternative DVA initiative. Ane is an original IRIS trial intervention civic (F) that commissioned IRIS after the original trial. Additionally, an urban northern IRIS area (Thousand) had an IRIS service started inside the study period. The personnel involved included all staff at each general practice (clinical and administrative), DVA service providers' staff and commissioners, including NHS clinical commissioning group staff (clinical leads for kid/developed safeguarding and women's health) and local council staff (concerned with local DVA strategy and public health).

Population/ participants

Sites are invited to take office in this research due to their geographical location in the North Thames area of London, adjoining the original IRIS intervention trial site with a priori knowledge that areas are interested in IRIS commissioning. 1 IRIS site outside of London is included as a qualitative example study, equally it fulfilled pre-specified inclusion criteria of this work (meet Appendix A). IRIS targets women affected by DVA, either currently or historically, from a partner, ex-partner or an adult family member. The eligibility criteria to be included in this observational study are: female patients aged 16 and higher up, registered at a general exercise, at the sites being studied. Women affected by DVA are identified by a clinician and offered a referral to the named IRIS abet-educator (AE); or women tin can cocky-refer to IRIS if they see the publicity cloth displayed inside a surgery.

Intervention

IRIS is a general practice-based DVA training, back up and referral programme for primary care staff. The theoretical framework of the training is based on educational outreach, adult learning theory and peer influence. It was developed using the MRC framework for complex interventions, to improve the chief care response to DVA. This involved steps for development, piloting and testing the intervention in a trial blueprint followed by implementation in routine full general exercise [26].

The IRIS model consists of five cadre components:

- 1.

Practice based DVA training, with ii 2-hour sessions for the whole do team.

- 2.

A local GP, interested in DVA, appointed as an IRIS clinical lead (CL) delivers clinical training alongside an IRIS AE.

- three.

A named DVA specialist – an IRIS AE - employed and based in a local DVA service, delivers grooming and also receives referrals from clinicians, responsible for a caseload of work, providing on-going support, refresher grooming and consultancy for the entire practice squad, on a day to day basis when in the practice (preferably attending regular quarterly do meetings), past phone and electronic mail.

- 4.

The AE sees women affected by DVA, providing skillful advocacy, including gamble assessments, safe planning, emotional & mental health support, housing advice, referring, (e.g. to multi-agency risk assessment conferences (MARACs), child safeguarding services), back up on injunctions & criminal justice organisation, signposting (east.one thousand. to specialist DVA legal services) and accompanying to police or courts.

- 5.

An electronic prompt, reminds clinicians to ask about DVA, considering its multiple dimensions [28] and a template within which to tape DVA (encouraging clinicians to (i) assess the firsthand safety of the woman and any children, (ii) offer referral, (3) review within general exercise). The electronic prompt is triggered by codes for health conditions or symptoms associated with DVA, such as fatigue, insomnia, anxiety and depression.

The AE is an experienced specialist support DVA worker, with previous training experience. The CL is interested in DVA every bit a health outcome, preferably also with training experience. Both the IRIS AEs and CLs have completed the national IRIS Training for Trainers programme, delivered by IRISi staff, Footnote 1 over 3 and two days respectively. The IRIS model is based on one total-time AE working with 25 full general practices. The model is congenital upon partnership piece of work, with primary care and specialist third sector agencies meeting to deliver services and promote work across the interdisciplinary gap. Further details about training (e.g. flowcharts showing simple referral pathways and various IRIS publicity materials to display in practices) are given in Additional file i.

Comparator intervention

The culling DVA intervention delivered in the comparator site, Due east, too comprised a DVA education package. This involved training delivered away from full general practices, training was delivered by those from an advocacy background (not clinicians), clinicians' referrals were sent to a One Stop Shop (not named advocates), with no electronic prompt embedded within the electronic medical record, encouraging clinicians to ask nigh DVA when clinically relevant. The comparator site was non chosen at random. Information technology was invited to participate in this research considering it had declined to committee IRIS, but had commissioned an alternative DVA didactics package.

Outcomes

Effectiveness outcomes

The chief event measure is the number of referrals received by DVA service providers from general practices. The denominator is the number of women anile 16 years and to a higher place within the practice. This is an evidence-based, intermediate outcome mensurate, on a causal pathway towards decreased DVA, and possibly ameliorate mental health and improved quality of life for women who are referred to specialist DVA services [12].

The secondary outcome measure is the number of women in whose medical records electronic DVA codes, representing DVA identification are used. The denominator is the number of women aged 16 years and to a higher place registered inside each practice. Other pre-specified secondary outcome measures are the number of referrals received by MARACs from full general practice, the type of contact and back up offered to women by DVA advocates.

Procedure outcomes

Context for IRIS implementation, factors influencing IRIS implementation, local adaptations of IRIS and the reach of IRIS training is examined, at the northeast London IRIS sites - A, B, C, D and F.

Qualitative outcomes

Theoretically informed analysis of the features contributing to sustainable implementation of IRIS is conducted at sites B and 1000 (see Appendix A).

Information sources, drove and management

Quantitative data

We employ historic and prospective information routinely nerveless from multiple sources:

- 1.

DVA service providers: number of referrals received past their DVA workers, from general practices, with the date that each referral is received, the full general practice from which it is received, the type of contact that is and then made and the type of back up required.

- 2.

IRIS AEs: tape data in referral spreadsheets, with each referral received, the referral date, the practice from which information technology is received, the contact type and support blazon, including whether a referral is made to a MARAC. They as well tape the dates of all IRIS training delivery, the number of practice staff that attend and who specifically delivers the grooming. These paper based records, are electronically entered on to spread sheets and shared with the researchers either straight or via IRISi.

- 3.

Full general practices' electronic medical records (EMR) for DVA codes used, each code with a date postage stamp and the general practice, at which information technology was used. EMR searches and information extraction are carried out remotely using the EMIS (Egton Medical Data Systems) web system located in the Heart for Primary Care and Public Health, Queen Mary, Academy of London.

- 4.

Electronic searches conducted centrally extract the number of women anile 16 years and above registered at each general practice and the Index of Multiple Deprivation score.

- 5.

Online anonymous questionnaire survey, incorporating an implementation measure based on Normalisation Process Theory [29] and administered via the Bristol Online Survey (BOS) tool (https://www.onlinesurveys.air conditioning.u.k./).

- 6.

A five-item checklist assesses the allegiance of IRIS, identifying IRIS' local adaptations.

-

Is DVA training practise based?

-

Is a local GP, the IRIS CL, delivering training alongside the AE?

-

Is the IRIS AE, based in a local DVA service?

-

Is the IRIS AE delivering training & receiving referrals?

-

Is the electronic prompt & recording template, been activated?

-

- vii.

Exercise websites for the total number of practice staff employed. All contained a listing of exercise staff.

All extracted data are entered into the written report database for statistical analysis.

Qualitative data

Qualitative data are derived from the free text comments generated by the online anonymous questionnaire survey (see to a higher place), participant ascertainment, document analysis and interviews – semi-structured, using purposive samples of general practice staff (clinical and non-clinical), AEs, local stakeholders, including commissioners and IRIS service users. This work describes and understands rationale for any features unique to a detail site, capturing the views of professionals involved in implementing IRIS and patients who have been referred into the IRIS service.

Data analysis

Quantitative information analysis

Sample size

The sample size was determined by simulation, using the SimSam parcel in Stata [30]. Simulations were of an analysis of monthly counts with a Poisson distribution. We assumed a typical practice had an average referral charge per unit at baseline of 4.5 per 100,000 per month, based on data from the IRIS cluster randomised trial [9], with this rate varying between practices with a 95% normal range of one.seven to 12.two per 100,000 per month. We further assumed there were 3000 eligible women per exercise, and 180 practices. We determined the number of months of data required to detect a doubling of the referral rate following the introduction of the intervention, with xc% power at the 5% significance level, assuming that different practices introduced the intervention at dissimilar times, uniformly over this flow. Simulation showed that 17 months of data were required. In order to capture whatsoever seasonality in the referral rates we increased this to 24 months.

We use an interrupted time serial segmented regression approach with a mixed furnishings Poisson regression model, to examine the upshot of the IRIS intervention on the primary outcome measure (the number of referrals received past DVA service providers from full general practices); and the secondary consequence mensurate (the number of first times that DVA identification electronic codes are used in medical notes by clinicians). We compare these outcome measures earlier and later the appointment of the kickoff IRIS training session, taken from individual general practices (i.eastward. practice level information), from multiple general practices. This engagement of the kickoff IRIS training session is taken equally the date of IRIS implementation.

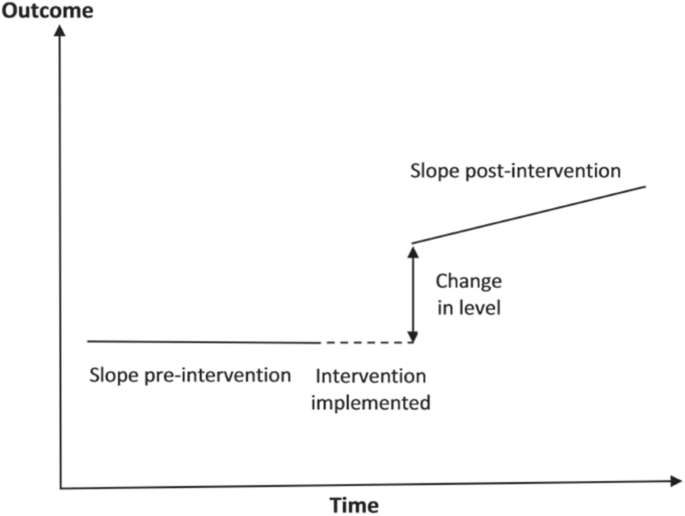

Figure ane depicts an interrupted time series segmented regression arroyo. Using this approach it is possible to examine whether in that location is a change in level immediately and/or a change in regression slope post-obit the implementation of the intervention, i.due east. a change in the gradient of the slope pre- and postal service-intervention.

An interrupted time series segmented regression approach

For each exercise the outcomes are defined every bit a daily frequency. The observations occurring on the day that the training is received are excluded, as information technology is not possible to say whether these occurred before or later preparation. Graphical displays of the information prove average daily rates (per 1000 people) plotted against fourth dimension centered on IRIS implementation. A moving average smoothing part, with equal weights, is applied to the information, with an unadjusted line of best fit added, earlier and later on the grooming.

The ITS model includes a random effect of practice and fixed furnishings of training (pre or post in any given day in any given practice), the slope of the underlying time trend, the alter in gradient following the grooming, site (five London boroughs), and calendar month and day of the week to allow for any seasonal issue of time. If for either outcome measure there is show of over-dispersion of the daily frequencies compared with a Poisson distribution then we model this with a random event of day nested within the random effect of do. We besides adapt for the log-transformed number of women aged 16 years and in a higher place registered at that practice, every quarter, as an first variable in the analysis. This allows us to control for the bachelor population size at whatsoever one fourth dimension. The analysis includes only those general practices that received IRIS training. We exclude practices where fifty% or more than of the list size data are missing, meaning we practise not know the number of women aged xvi years and above registered at the do. Regression coefficients are presented every bit incidence rate ratios. Data is analysed using the Stata V14 package (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Sub-group analyses

A priori additional analyses include comparison the different implementation sites (A, B, C & D) to each other and the comparator site (E). The ITS assay is run separately within each site. A woods plot is used to compare these individual analyses. Deprivation scores are used to check that deprivation does non confound the results.

Process evaluation data assay

Survey data are exported from BOS to Stata V14 and analysed using descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations and frequencies) for the quantitative data.

Qualitative data analysis

Interview data are transcribed verbatim and coded thematically, using a mixture of anterior and deductive approaches. Theoretically informed analysis is conducted. Significant patterns are identified and the data examined for deviant cases.

Knowledge mobilisation

We propose to present the findings from this study to key stakeholders at multiple local, national & international, non-bookish and academic, conferences, meetings and workshops. Nosotros volition besides report our findings in academic and non-academic publications, sharing with national and international wellness policy fora, including contributions to the Britain Government's planned landmark Domestic Abuse Bill. The terminal IRIS ITS analysis results, supported with qualitative insights and web-based publicity will exist presented to our local partners, including healthcare professionals, IRIS CLs, IRIS AEs, their managers and local third sector DVA host agencies, as well equally local health intendance commissioners based in CCGs, Public Health, Local Authorities and the Police & criminal offense commissioners whilst highlighting their role in integrating commissioning, using strategic partnerships.

Give-and-take

This is the beginning interrupted fourth dimension serial assay of an intervention to improve the health intendance response to domestic violence. The findings of this observational segmented regression interrupted time serial assay of GP IRIS implementation, exterior a trial setting will characterise its suitability for national implementation in the Britain. It volition inform decisions well-nigh the future commissioning of IRIS in the UK. If the findings are positive, this will support the more widespread commissioning of IRIS despite the on-going constraints of thrift that are disproportionally reducing women's services https://www.theguardian.com/earth/2017/mar/09/women-bearing-86-of-thrift-burden-labour-research-reveals. Comparison of the implementation sites, using integrated quantitative and qualitative findings may help us understand the core components of IRIS that should be retained in the plan when commissioned locally or nationally so that the bear on of IRIS is not diluted. If the findings are non positive and so conscientious idea is required to consider what should be the next step, on what has been a difficult path, on the rough terrain of improving the healthcare response to DVA.

Notes

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

advocate-educator

- BOS:

-

Bristol Online Survey

- CL:

-

clinical lead

- DVA:

-

Domestic violence and corruption

- EMIS:

-

Egton Medical Data Systems – initial non used again

- EMR:

-

electronic medical record

- IRIS:

-

Identification and Referral to Improve Safety

- ITS:

-

interrupted time series

- MARAC:

-

multi-bureau risk assessment conferences

- NICE:

-

National Plant for Health and Care Excellence

- QALY:

-

quality-adjusted life years

- WHO:

-

Earth Health Organization

References

-

WHO. Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: who clinical and policy guidelines. 2013.

-

National Plant for Health and Care Excellence. Domestic violence and abuse: multi- agency working Dainty guideline. 2014.

-

Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, Abbott JT. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997 May 7;277(17):1357–61.

-

Johnson JK, Haider F, Ellis 1000, Hay DM, Lindow SW. The prevalence of domestic violence in pregnant women. BJOG. 2003 Mar;110(3):272–5.

-

Bacchus LJ, Bewley Southward, Vitolas CT, Aston One thousand, Hashemite kingdom of jordan P, Murray SF. Evaluation of a domestic violence intervention in the maternity and sexual health services of a U.k. hospital. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:147–57.

-

Raissi SE, Krentz HB, Siemieniuk RA, Gill MJ. Implementing an intimate partner violence (IPV) screening protocol in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015 Mar;29(3):133–41.

-

Warren-Gash C, Bartley A, Bayly J, Dutey-Magni P, Edwards S, Madge S, Miller C, Nicholas R, Radhakrishnan Southward, Sathia L, Swarbrick H, Blaikie D, Rodger A. Outcomes of domestic violence screening at an acute London trust: are there missed opportunities for intervention? BMJ Open up. 2016 Jan four;6(ane):e009069.

-

Rose D, Trevillion K, Woodall A, Morgan C, Feder One thousand, Howard L. Barriers and facilitators of disclosures of domestic violence by mental health service users: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011 Mar;198(3):189–94.

-

Feder G, Davies RA, Baird M, Dunne D, Eldridge South, Griffiths C, Gregory A, Howell A, Johnson M, Ramsay J, Rutterford C, Abrupt D. Identification and referral to improve safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and back up programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011 Nov;378(9805):1788–95.

-

Colombini One thousand, Mayhew S, Watts C. Wellness-sector responses to intimate partner violence in depression- and middle-income settings: a review of current models, challenges and opportunities. Balderdash Globe Health Organ. 2008 Aug;86(8):635–42.

-

Hegarty G, Taft A, Feder G. Violence between intimate partners: working with the whole family. BMJ. 2008 Aug 4;337:a839.

-

Rivas C, Ramsay J, Sadowski L, Davidson LL, Dunne D, Eldridge S, Hegarty K, Taft A, Feder G. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-existence of women who experience intimate partner corruption. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Dec three;12:CD005043.

-

Devine A, Spencer A, Eldridge S, Norman R, Feder Grand. Cost-effectiveness of identification and referral to improve safety (IRIS), a domestic violence training and back up programme for primary care: a modelling study based on a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open up. 2012 Jun 22;2(three):Pii:e001008.

-

Malpass A, Sales K, Johnson G, Howell A, Agnew Davies R, Feder G. Women's experiences of referral to a domestic violence advocate in UK chief intendance settings: a service-user collaborative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014 Mar;64(620):e151–8.

-

Yeung H, Chowdhury N, Malpass A, Feder GS. Responding to domestic violence in general practice: a qualitative report on perceptions and experiences. Int J Family Med. 2012;2012:960523.

-

HM Government: Catastrophe violence against women and girls Strategy 2016–2020: London, 2016.

-

Davies SC. Almanac report of the chief medical officer, 2014, the health of the 51%: women. London: Department of Wellness; 2015.

-

Domestic Homicide Review: lessons learnt. Home Office 2013.

-

Vos T, Astbury J, Piers LS, Magnus A, Heenan M, Stanley L, Walker L, Webster K. Measuring the impact of intimate partner violence on the health of women in Victoria. Australia Balderdash Globe Health Organ. 2006 Sep;84(9):739–44.

-

Devries KM, Mak JY, García-Moreno C, Petzold Thousand, Kid JC, Falder Yard, Lim South, Bacchus LJ, Engell RE, Rosenfeld Fifty, Pallitto C, Vos T, Abrahams Due north, Watts CH. Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence confronting women. Science. 2013 Jun 28;340(6140):1527–8.

-

Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–6.

-

Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Chung WS, Richardson J, Moorey S, Feder 1000. Abusive experiences and psychiatric morbidity in women primary care attenders. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:332–ix.

-

Walby Southward, Towers J, Francis B. Is violent crime increasing or decreasing? A new methodology to measure echo attacks making visible the significance of gender and domestic relations. Br J Criminol. 2016;56:1203–34.

-

Sohal AH, James-Hanman D. Responding to intimate partner and sexual violence confronting women. BMJ. 2013 Jun xx;346:f3100.

-

Walby Due south, Olive P. Estimating the costs of gender-based violence in the European Union: European Establish for Gender Equality, 2014.

-

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre South, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating circuitous interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008 Sept 29;337:a1655.

-

Campbell Thousand, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, Tyrer P. Framework for blueprint and evaluaton of circuitous interventions to improve wellness. BMJ. 2000 Sep 16;321(7262):694–6.

-

Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder One thousand. The sensitivity and specificity of iv questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accurateness study in general do. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49.

-

Finch TL, Rapley T, Girling Chiliad, Mair FS, Murray Due east, Treweek Due south, McColl E, Steen IN, May CR. Improving the normalization of complex interventions: measure development based on normalization process theory (NoMAD): study protocol. Implement Sci. 2013 April 11;viii:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-43.

-

Hooper R. Versatile sample size calculation using simulation. Stata J. 2013;13(i):21–38.

Acknowledgements

We are about grateful to the practitioners delivering IRIS in each local surface area, including the full general practice staff, IRIS CLs, IRIS AEs, their managers, the 3rd sector DVA host agencies and commissioners based in CCGs, Public Health and Local Authorities. Jack Dunne and Martin Sharp, from the Clinical Effectiveness Grouping, based at Queen Mary, helped us to plan and conduct EMR searches and data extraction, using the EMIS web organisation.

Funding

This enquiry is funded past the National Found for Wellness Enquiry (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames at Bart's Health NHS Trust (NIHR CLAHRC North Thames). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and non necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Wellness and Social Intendance. The costs of funding IRIS in each local area are covered by a diverseness of bodies including CCGs, Public Wellness and Local Authorities.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated, used and analyzed during this written report are bachelor from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The datasets are contained in the Barts Cancer Middle repository.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

AS had the original idea for the study, leads this study, writing the first and terminal draft. AS, CG, GF, NL & SE designed the ITS and other aspects of the report. NL designed the process evaluation. Advertisement designed the case studies. MJ and AH deliver some of the core components of the intervention (e.g. Training the Trainers course), also assisting with developing the report thought and information drove. KB provides communication on how best to collect data from the EMR. Equally collects data for the ITS, NL for the PE and AD for the case studies. Iron assists with data collection, constructs the database, organizes and manages data collected. CN & LB planned the statistical assay of the data, with CN calculating the sample size, both supervised by SE. All authors are members of the study group, substantially contributing to the study's conception, design, development and the manuscript's revision and refinement. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript. AS and GF are the guarantors of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approving and consent to participate

The process evaluation and qualitative study piece of work has ethical blessing from the London Enquiry Ethics Committee, Queen Mary University of London (QMREC1799a: 25.08.16; & QMERC2015/29a and QMERC2015/29b: 30.07.15 respectively), with the former also approved by the NHS Wellness Enquiry Authorization (16/HRA/4398: 13.10.2016). All interview participants provide written informed consent.

The quantitative ITS evaluations merely utilise anonymised data, arising from the usual care of women so individual consent of women is non required. This decision and study is approved by the Chair of the NHS London Camden Research Ethics Committee, equally an evaluation of usual care.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AH and MJ were DVA IRIS AEs, at time of original IRIS trial; and are at present both funded to facilitate commissioning of IRIS in the UK, with MJ the CEO of IRISi. Positive trial findings would support their career development. GF is on the IRISi board. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher'southward Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Appendix

Appendix

Pre-specified case written report inclusion criteria

The post-obit inclusion criteria are used to determine sites to be included as a instance written report:

-

Sites not involved in the original IRIS trial

-

Sites that had commissioned IRIS for more than than two years

-

Sites that are not anomalous in their delivery of IRIS - based on give-and-take with the IRIS Implementation team

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilize, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided yous give advisable credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Sohal, A.H., Feder, G., Barbosa, Eastward. et al. Improving the healthcare response to domestic violence and abuse in primary care: protocol for a mixed method evaluation of the implementation of a complex intervention. BMC Public Health eighteen, 971 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5865-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5865-z

Keywords

- Domestic violence abuse circuitous intervention implementation evaluation

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-5865-z

0 Response to "Addressing Safety in Domestic Violence in Primary Care Peer Review"

Postar um comentário